What sort of will do you actually need?

Helen Edwards, Andrew Coffin, Faith Siaw

Couples typically want “simple” wills, at least to begin with. However, there are often unspoken assumptions built in which make things far harder. For example, putting aside assets to pass to children from your first marriage after you and your partner die does not guarantee those children will receive the assets if your partner changes their will after you die.

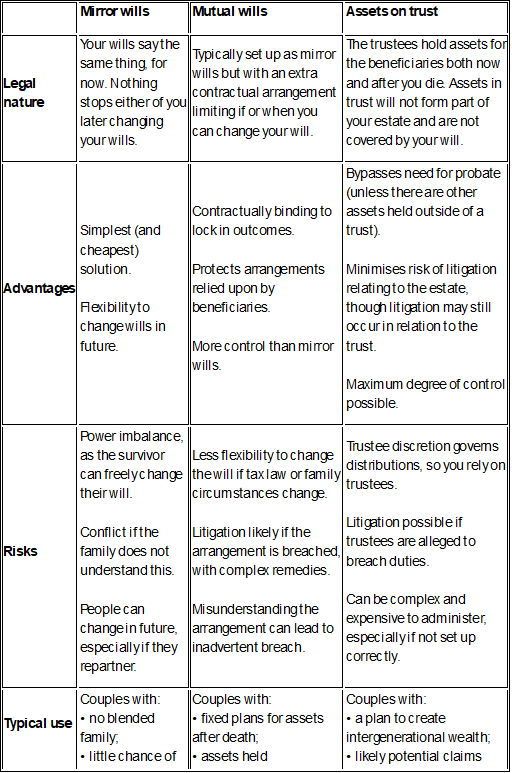

This table summarises some of the differences partners should be aware of when considering whether to use mirror wills, mutual wills, or, alternatively, placing assets in a discretionary trust:

Mirror wills

Mirror wills are two wills that have the same effect. In short, they mirror each other. It doesn’t matter who dies first or second – the same overall effect is achieved. However, as wills are revocable, at any point you can change what yours says. You might make your will as a mirror to your partner’s will, but that doesn’t stop either of you from changing it after the other dies. This creates a power imbalance, as the first person to die (and the other surviving beneficiaries) relies on the survivor to respect their wishes.

Other issues can arise where the survivor has no choice but to depart from the deceased’s wishes. For example, if the survivor enters a new relationship and fails to sign a contracting-out agreement, their new partner may later claim half the assets built with the first spouse upon separation (provided those assets have become relationship property of the new relationship). Another example is if the survivor is sued – their personal assets subject to the claim include assets built with the deceased partner.

While mirror wills are the quickest to draft, and therefore the cheapest of these arrangements, care is needed to ensure you understand the risks, are comfortable with them, and that your family also understands. We have routinely seen children in blended families disappointed at a survivor’s decisions on how to spend or allocate assets built with the deceased, and asking how the survivor is permitted to do this. These situations are a magnet for litigation and fractured family relationships.

Mutual wills

Mutual wills are relatively rare in New Zealand despite being a powerful estate planning tool. They sit on top of your will as a contractual arrangement locking certain provisions in, preventing either of you from changing them. However, the devil is in the detail: what you lock in, how you lock it in, and in what circumstances it applies.

One thing to consider is the extent to which you want to constrain the survivor from using assets as they please. Most people want to provide for their partner if they die, and the more limits you place on them, the harder this becomes. Typically, mutual wills would not prevent a survivor from spending assets built with the deceased on themselves – for example, a round-the-world tour. In contrast, mutual wills would typically stop the survivor gifting everything to a favoured child, which would otherwise leave nothing for the other children when the survivor eventually passes.

Mutual wills can be complex to set up and to get right, but they give you an extra degree of assurance that your testamentary intentions will be respected after you die. However, they can also be complex to enforce and are not always properly understood, which can create problems.

Family trusts

Another option is to gift your assets to a family trust for beneficiaries, typically yourselves, your children and grandchildren. This approach means that the trustees are the legal owners of the assets in trust, so no probate is required to access them after you die. Removing assets from your personal ownership and placing them in the trust reduces the assets available for estate claims, thereby minimising the risk of estate litigation. When people seek to disinherit a child, they will often put assets into a trust which does not have that child as a beneficiary.

Family trusts create their own problems. You may avoid estate litigation but invite trust litigation from beneficiaries dissatisfied with trustee decisions, alleging that trustees have breached their duties. Care is required to set trusts up correctly and maintain them properly. Further, being a trustee can be risky, even if you have broad discretion in how you deal with trust assets, given the duties owed. The Trusts Act has made it easier for beneficiaries to request information, further opening the trust structure to oversight.

There are rumblings of potential law reform in this area, with the Law Commission proposing substantial reforms to make it harder to use trusts in this way. While nothing has occurred yet, anti-avoidance measures are being considered to limit the ability of parents to effectively disinherit children using trusts.

Final thoughts

Estate planning is not just about having a will. It is about choosing the right tools – whether mirror wills, mutual wills, or trusts – to protect the people and values that matter most to you. Misunderstandings or poorly structured documents can lead to family conflict, costly litigation, and outcomes no one intended. Getting the right advice early is not just prudent, but essential.

If you are unsure whether your current will achieves what you want, please get in touch and we can review it for you.